🥟 Relearning China: Part 1

What I’m unlearning and relearning before my trip to Shanghai

In a few days, I’ll be in Shanghai for a one-week course to study China’s innovation ecosystem at Fudan University! DM me if you’re there, I’m organising meet and greets!

As a Hong Kong Chinese, there’s a lot to unpack. Given our decades of historical separation, I’ve found that for a place as China, the most critical work isn’t just learning. This trip isn’t about collecting new facts or finding easy answers. My real intention is to unlearn old assumptions, and make space to relearn.

So, before I go, I wanted to share what that process looks like ☻

Relearning About Chinese Consumption 👀

I was discussing China’s macroeconomic landscape with an officer from the Hong Kong government who is based in Singapore. A keyword came up. It’s not new, but it continues to define today’s zeitgeist: 内卷 (nèijuǎn).

It’s a term for the intense, internal competition in China. A culture in which people feel they are working harder just to stay in the same place. The result of living in a state of nèijuǎn is a widespread feeling of burnout, exhaustion, and psychological strain. People who are exhausted and feel their hard work isn’t paying off become more practical and protective of their resources. Their priorities shift away from frivolous purchases towards things that offer real, tangible value and comfort, fuelling 理性消费 (lǐxìng xiāofèi, or ‘rational consumption’). This mindset is manifested in two dominant signals:

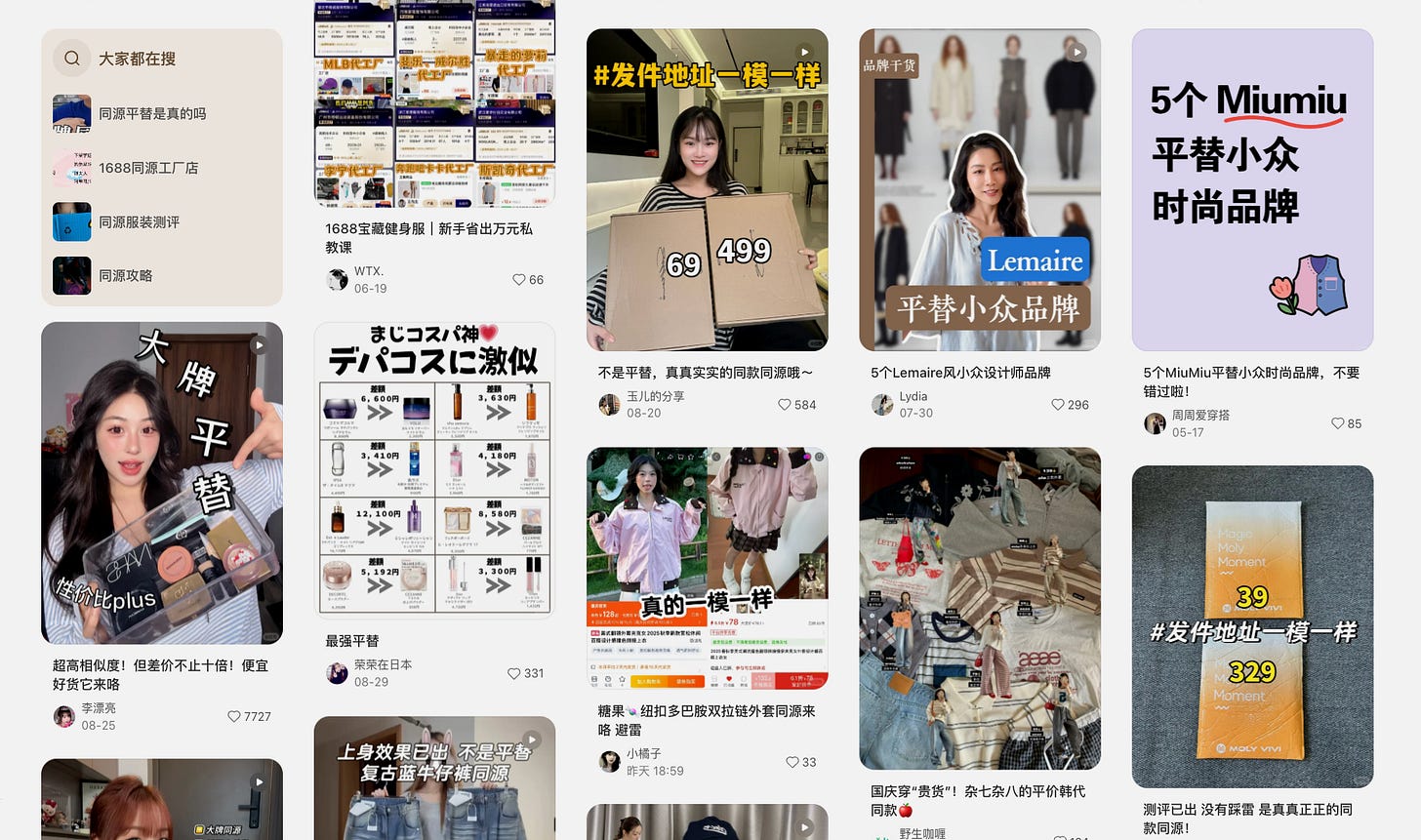

First, the hunt for 平替 (píng tì), as known as affordable, high-quality substitutes, often perceived as a ‘smart replacement’ for an expensive product. This led to new forces such as: 平替网红 (píng tì KOL – influencers such as @平替君 who build a following by finding and reviewing high-quality, affordable alternatives), 同源平替 (an affordable product that is made in the same factory or with the same materials as a premium brand), 海外好物平替 (alternatives to popular foreign products), and ofcourse, the latest evolution of all: 替中替 (tì zhōng tì), which literally translates to ‘the substitute for the substitute’, meaning the even more affordable alternative to the already-affordable píng tì.

Second, the movement against 智商税 (zhìshāng shuì), or ‘IQ Tax’, a slang term for the feeling of being tricked into paying for brand hype over real value. Chinese netizens are actively calling out brands (foreign and domestic) for it, creating content to help each other 避雷 (bì léi), literally to ‘avoid the thunder’ of bad or overhyped products. Guess which brands are commonly associated with IQ Tax?

An attempt to unpack this, my conclusion is: Chinese consumers are proud to find a product that delivers a premium product’s performance for a fraction of the price. Finding a great píng tì is a sign of intelligence, while paying ‘IQ Tax’ is foolish. On a less serious note, comedian Jimmy O Yang joked about this (please watch the clip till the end. I agree with his observation…the part about Asians ☻)

This combination of 内卷 (nèijuǎn), 理性消费 (lǐxìng xiāofèi), 平替 (píng tì), 智商税 (zhìshāng shuì) and 避雷 (bì léi) leaves businesses with a critical question: What might be the new winning vision and reason to exist in China?

Unlearning Winning Recipes 👀

Almost 12 years ago, I had a Chinese beauty client. They were pretty successful at the time, in fact, they were one of the top cosmetics brands in the country. In an effort to refresh their brand identity, they aspired to look ‘French’. Key stakeholders insisted adding a faux accent mark in the logo to signal ‘French-ness’.

Their thinking was clear: Western means premium quality. And this thinking made sense, because it was part of a bigger global picture. In the 2010s, there was really only one question that mattered to global businesses:

How can we sell in China? The underlying assumption for everyone, both local and global, was that Western brands held the keys to aspiration. For global brands, ‘Western-ness’ was a primary marketing asset. The strategy was to enter the Asian market with this built-in advantage, localising tactics like packaging or celebrity choice, but never the core aspirational promise itself. For local brands, the goal was often to emulate that dream. This is exactly what I saw with my beauty client wanting a faux French logo. They were using a Western code to signal ‘premium’ in China because that was a shared definition of quality.

Fast forward to today, that question becomes:

How can we compete with local Chinese brands?This shift is happening because the very definition of ‘aspiration’ has been inverted. The winning local brands, from beauty to food & drinks to fashion, have stopped selling the Western dream and are now selling local confidence, rooted in their own craft, history, and a proud Chinese identity. On top of that, companies like Proya are not just winning at home. They want to go global.

It’s probably one of the first cases where a Chinese conglomerate went from thinking, ‘Okay, I’m just happy being one of the biggest in China,’ to saying, ‘Well, we actually now want to become a global conglomerate.

Ariel Ohana, Managing Partner of Ohana & Co.

For a global sweet confectionary client, the latest question we are exploring is even more directional:

How are Chinese trends rippling into the rest of Asia?This evolution from a Chinese brand wanting a faux French logo to a global brand today studying Chinese trends is a fundamental inversion of the flow of cultural and commercial influence. Perhaps the real anxiety for a global consumer business isn’t the fear of a failed product launch or campaign in China. Maybe it’s the quiet discovery that the old playbook no longer exists.

Having been in Asia’s consumer brand and innovation landscape since my first job, witnessing this evolution firsthand is humbling ☻

Relearning How to Study China 👀

Media like to show us what is happening in China, but rarely the why. And the why in China is crucial, as so much of the market operates on 情绪价值 (qíngxù jiàzhí), or ‘emotional value’ these days. To understand qíngxù jiàzhí, we have to look beyond surface-level trends. We have to understand China’s 底蕴 (dǐyùn).

There’s no perfect English word for it. The closest translation is the ‘deep, underlying foundation’ or the ‘real substance’ of a culture. It’s an invisible code, often written over thousands of years, that runs in the background of society. It shapes how people build relationships, perceive value, define success, and communicate with each other.

My journey to grasp this has been deeply inspired by the work of Chinese scholars, such as 南懷瑾 (Nan Huai-Chin). His genius was in his integrated understanding of how China’s three core philosophies (Confucianism, Daoism, and Buddhism) intertwine to shape culture. In this book, he defined the foundation of Chinese culture as four elements: Speech, Written Language, Way of Thinking, and Habits of Life.

文化的基础是什麼?我的定義是言語,文字,思想(思維方式),生活習慣,這四個要素的構成就是文化。

南懷瑾 (Nan Huai-Chin),

He also offered a more classical view from Confucius, who defined the pillars of Chinese culture as: Virtue, Speech, Political Affairs, and Literature.

如照孔子當時的分科,它是德行,言語,政事,文學四方面來概括人文文化。

南懷瑾 (Nan Huai-Chin)

All of this may sound super old-school (👵🏼)… But as I dig into these ideas, I realised they are still very valid frameworks for any brand trying to navigate China today. Each of these elements can be translated into everything we need to know about China:

Speech: slang, tone of voice, jokes, questions

Written Language: hashtags, emojis, commentary

Way of Thinking: the “why” behind the “what"

Habits of Life: rituals, lifestyle, habits

Political Affairs: ecosystems, relationships, agendas

Literature: books, music, film, new mediaIt’s tempting to use familiar business frameworks to study China. But what I am doing differently today is pushing myself and my team to study Chinese nuances through emojis, jokes, slangs, hashtags, habits, reviews, commentary etc… and unpack culture from there.

I am going to meet a few business leaders on the ground to dig deeper into these topics and explore as I go. Stay tuned for Part 2!

…

Last but not least, happy mid-autumn for anyone who celebrate.

中秋節快樂 🥮

Love how you connected these ideas together in this very insightful post! It’s fascinating to me that both 情绪消费and 理性消费/平替coexist in the same consumption universe in China. I’ve been thinking a lot about the profound emptiness, or the prevalence of the idea of”空心病”hollowness fits into all of this.

Dumpling: I enjoyed this thoughtful essay, especially because 蘊 and 底蘊 have featured in some of my work. See, for example,

http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/glossary.php?searchterm=029_yun.inc&issue=029

And,

http://www.chinaheritagequarterly.org/features.php?searchterm=019_whatspossible.inc&issue=019

Geremie